The Heat Is On

Preparing for a carbon-constrained world: Measuring carbon emissions along the value chain

By Peter J. Nieuwenhuizen, Philip W. Beall, and Davide Vassallo of Arthur D. Little

The heat is on. The climate debate has now well and truly moved beyond the question of whether climate change is happening or not. Science continues to address the inherent uncertainties of the field and challenge the limits of our knowledge, but societal opinion and perceptions have firmly shifted. No longer are we asking whether there should be limitations on emissions, but when and how. Such limitations, whatever form they take, will impact business by imposing costs or necessitating emission reductions. Climate change, in short, has become a business reality, to which companies must react.

As a consequence, business executives are asking themselves question such as: How should my company prepare for a carbon-constrained world? Do I know how much CO2 my company emits to make the products it depends upon? Do I know how much CO2 was emitted to produce the raw materials I buy? What is my total financial exposure once CO2 is fully priced in? And how does my company stack up against others, fulfilling customer demands and requirements?

To help answer these questions, this article will explain:

- why companies need to look beyond their own operations to determine their carbon exposure

- what a product carbon footprint looks like, and what is driving its emergence

- how companies can prepare to do business in a carbon-constrained world.

What is at stake?

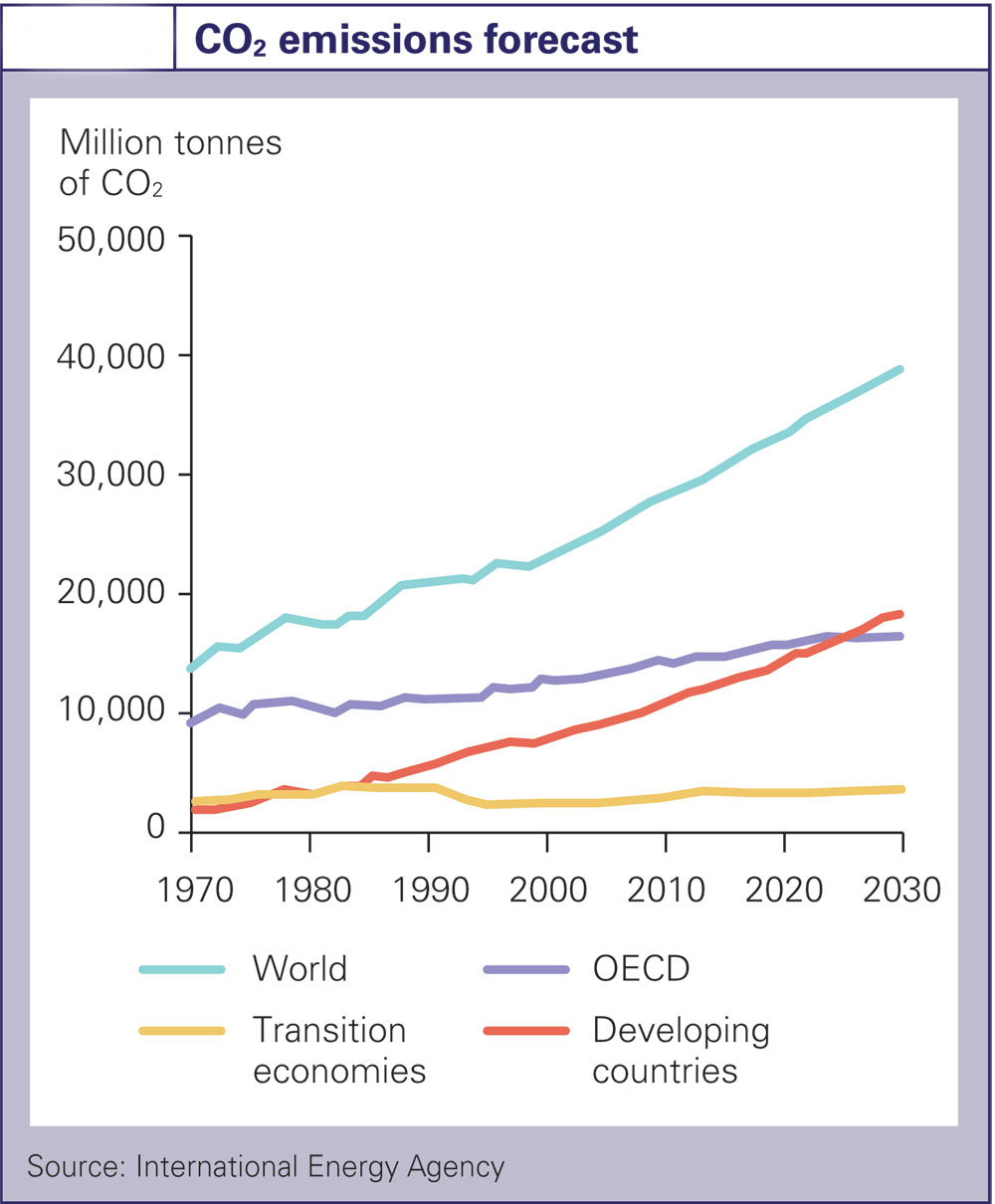

Without action global emissions are forecast to double by 2030 (fig. 1). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the advisory body to world leaders, concluded last year that global carbon dioxide emissions would need to fall by 50–85% by 2050 to prevent average global temperatures from rising more than 2°C. In the short and medium term, much of the emphasis to act will be on the developed economies of Europe, North America, Japan and Oceania. These OECD countries, home to just a fifth of the world’s population, are responsible for nearly half of the world’s annual CO2 emissions. Significantly, post 1900, they have caused over 70% of all CO2 emitted into the atmosphere (fig. 2). Since OECD economies generate nearly 60% of the world’s GDP, it is not difficult to understand why developing economies, even though their emissions are growing rapidly, expect OECD countries to reduce emissions sharply. To ‘make room’ for their fair share of emissions as they develop their economies, the OECD countries should mathematically reduce by as much as 80–90%.

In fact, the developed world is taking up the challenge. The European Union’s Emission Trading Scheme (ETS), developed in 2005, is today the world’s largest single carbon market. Japan and Australia are looking to implement a similar scheme, and even in the US, where the federal government has been dragging its feet, eight north-eastern states have formed the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, while California is partnering with 10 other US and Canadian states in the Western Climate Initiative. All initiatives work to implement a cap-and-trade program, which will impose a price on carbon emissions.

Estimates about the future price of carbon vary from as low as €25 ($38) up to €150 ($200), with the consensus on the higher end of the scale. According to the International Energy Agency, the cost of carbon dioxide emissions would need to be at least $200 a tonne, many times today’s level of €28 ($44) a tonne, to deliver the cuts proposed by scientists to avert the threat of global warming. Another trigger for a rise is the €100-per-tonne fine that came into force last year with phase two of the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme. It will be imposed on companies who breach their ETS emissions limits, and who will have to purchase enough allowances to bring them back into line.

Wherever the price settles, the impact will be substantial. The world stands on the brink of a new era in which carbon emissions are no longer free. Given their wealth and emissions, OECD countries are first in line to put a true cost on carbon. At €28 per tonne, Europe’s total emissions, 2 billion tonnes in 2008, are costing some €56 billion, or approximately 0.5% of GDP (€12.7 trillion in 2008). This will impact on every company and consumer in these economies. As the costs for CO2 emissions cascade down the supply chain, there will be winners and losers. Products, processes and services that require few emissions will gain a cost and image advantage over those that require more; industries will scramble for access to scarce low-carbon resources, driving their price up.

Scoping company emissions

To understand their exposure, companies need to know how much carbon is emitted to produce their products or services. The good news is that many companies have already started doing so. Unfortunately, what is best practice today is only the beginning of what is needed to prosper in a carbon-constrained world.

Today, companies typically measure and report carbon emissions on an absolute basis, eg by production location, totalled by region and eventually by company. This is then reported, for example, in company annual reports or through dedicated initiatives; the not-for-profit Carbon Disclosure Project is the largest. Besides acting as a repository for company carbon emission information, it provides information to institutional investors with combined assets of over $57 trillion under management and, therefore, is a force to be reckoned with.

To provide additional insight, total company emissions may be divided by total production or sales to obtain a CO2 productivity ratio. This type of reporting is becoming more prevalent as companies set CO2 reduction targets using total production to normalize the ratios. An example is shown in figure 3 for three international oil and gas companies.

The emission-reporting initiatives have been developed as a result of joint efforts from business, governments, and independent stakeholders, including NGOs. They exist partly to allow emission trading and partly to create greater transparency, so that companies, as a first step to emissions control, can be benchmarked against each other. The reporting should comply with harmonized standards, the most influential of which are the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, pulled together by the World Resources Institute (set up by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development), and the ISO 14064 standard, compiled by the International Organization for Standardization. The standards are basically equivalent and both have been set up to create a global, harmonized standard to account for CO2 emissions. They divide company emissions into three scopes, as shown in figure 4.

Scopes 1 and 2 broadly correspond to emissions from energy use controlled by the firm. Scope 1 concerns direct emissions, eg a furnace that a company is operating. Scope 2 relates to indirect emissions, predominantly those from the electricity that is purchased and that has been generated by the combustion of primary fuels such as coal, oil or gas. Until very recently, scopes 1 and 2 were regarded the most relevant and all other emissions were lumped together as scope 3, and not widely considered.

While it is certainly good to report and minimize scope 1 and 2 emissions, this has two important disadvantages. First, it does not take into account the emissions related to raw materials that a company procures, and secondly, total company emissions do not convey how emissions relate to the different products or services a company provides.

As a result, the current system of emission reporting makes it nearly impossible to correctly benchmark companies regarding their ability to manage emissions. Comparing companies based on their aggregate scope 1 and 2 emissions works only in isolated cases when companies are homogeneous in their make-up. Scope 3 emissions need to be considered in order to gain a greater level of granularity and to compare emissions for products rather than companies.

Determining your product carbon footprint (PCF)

To help reduce carbon emissions, scope 1 and 2 emission reporting can only be seen as a first step towards a more sophisticated system of carbon reporting. Indeed, more companies are focusing on product carbon footprint (PCF) instead. PCF is the cumulative CO2 that is emitted along the value chain to make a particular product and deliver it to the customer. It is obtained by calculating all the emissions related to the raw materials and ingredients that a company’s product is composed of. To this is added the energy the company needs to manufacture the product and get it to the customer.

PCF is being evaluated by a number of leading firms, often in collaboration with NGOs. Each of these companies has realized that, as the world gets more serious and more sophisticated about managing carbon emissions, the only useful measure by which to compare companies is the total carbon footprint of the products they supply. But how is a PCF obtained?

The basic approach is:

- Determine the ingredients (or raw materials) for each product or service in scope, and how much is needed.

- For each ingredient, determine how much CO2 was emitted to manufacture and transport it to the customer.

- Determine the proportion of the company’s scope 1 and 2 emissions that each product requires, including transport.

- Add each element in the appropriate ratio to obtain the final value.

All this should be captured in an easy-to-maintain database so that companies can update their carbon footprint as they reduce their in-house energy use, or as suppliers improve the emissions of their products by changing to more efficient technologies or changing their raw materials. While conceptually quickly visualized, actual implementation requires serious work to gather the data, as well as decisions about the required accuracy of the data.

How PCF can affect your business

An ideal world in which each company can expect to receive from its suppliers an accurate carbon content for the products it buys is still a long way off. For the time being, those companies leading the way are required do some serious data evaluation to reliably inform their customers how much carbon they are buying. Not only do they have to determine how their own carbon emissions relate to the products they sell, they also need to do so for most of their suppliers, and suppliers’ suppliers, who may not have reached the same level of sophistication.

At this time, it is too early to tell whether product carbon footprinting will gain widespread acceptance among businesses, and to what extent it will be taken up by end consumers. But, besides the fact that leading consumer companies are driving the approach in their supply chain, there are some powerful drivers pushing business in this direction, some altruistic, some self-interested.

First, understanding the carbon content of their raw materials allows companies to become better at sourcing raw materials. In this time of energy cost hikes, knowing the carbon content allows companies to distinguish real energy-related price inflation from claimed hikes in the supply chain. In addition, when comparing suppliers, it will allow companies to partner with the ones that are most efficient or have certain natural advantages in terms of carbon.

Secondly, PCF can play a key role in the latest standardization initiative pursued by company stakeholders, such as WRI/WBCSD and ISO, the originators of the first scope emission reporting initiative. These organizations have embarked on a two-year process to develop industry standards for product and supply chain greenhouse gas emissions, allowing companies to quantify their scope 3 emissions. Businesses can expect that in two years’ time, scope 3 quantification will be actively promoted; for example, by the Carbon Disclosure Project, which has signed up as many as 3,000 leading firms around the world. Also, companies may be required to provide such information in order to receive high rankings in company benchmarking initiatives, such as the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI) or FTSE4Good.

Thirdly, stimulating PCF as a requirement to do business can be quite beneficial for incumbent, sophisticated companies that are competing with less well-run firms. PCF requires co-operation along the supply chain, a good understanding of manufacturing processes, and an ability to position and brand products. PCF will increase the complexity of doing business, and in doing so, well-run multinationals should expect to have an edge over their less-able competitors, at home and abroad.

Fourth, PCF can help companies to carve out valuable positions for marketing their products. A well-conceived ‘green’ marketing and product strategy can be very lucrative, and can provide a lasting edge over the competition.

Finally, PCF may help industry and governments deal with the thorny problem of ‘carbon leakage’. Carbon leakage occurs when companies, to escape potentially debilitating carbon costs, relocate their manufacturing operations from carbon-regulated OECD economies to others that do not (yet) impose a cost on carbon. The net effect would be a loss of employment in the country of origin and an increase in overall carbon emissions, since many developing countries employ less efficient and/or more carbon-intensive methods of energy generation. However, broad uptake of product carbon footprinting may allow governments to set maximum PCF values for products that are imported into their areas.

Executive insights

We are moving towards a world where carbon is constrained, and which will put a price on its emissions. This is set to be implemented first in the developed economies of the world, as developing nations argue they are morally allowed to increase their emissions to allow their current growth path. Already, many companies are measuring and/or reporting their carbon emissions. However, the traditional ‘scope-based’ framework is giving way to a value chain approach that is more sophisticated and considerably more insightful. Along the supply chain, companies will add up the carbon emissions specifically related to their products and services, thus providing a product carbon footprint, or PCF, which totals all upstream carbon emissions. This shift is being driven by some of the most well-known brands, is supported by NGOs and will ultimately allow comparison of the carbon efficiency of competing technologies, companies, and whole value chains.

So, how should forward-thinking executives prepare their companies? Three key actions are suggested:

- Determine the product carbon footprint for your products and services. As a first step, this can be done pragmatically, in an 80–20 fashion, planning to work out the details over time. It is better to have a rudimentary system that gives guidance, than the perfect system that is not yet operational.

- Appropriate the first-mover advantage, if still possible. Find out whether you can position your company as a leader in low-carbon products and services; strike up long-term supply deals with your most proactive or advantaged suppliers to make sure you pull their carbon advantage into your, not your competitor’s, supply chain; find out which of your customers are seeking to market low-carbon products and services and offer to join forces.

- Start reducing carbon. With the knowledge obtained through the above, reduce carbon in your company and value chain. Whenever Arthur D. Little have helped companies to do so, not only have technical and practical solutions been found for the majority of their emissions, but also a large proportion of the initiatives have added straight to the bottom line. This makes carbon footprint programmes self-funding, even profitable, right from the start.